In these current changing times, learning online has rapidly become part of our students’ lives. One element of using technology is accessing games. In the physical classroom we utilise mathematical hands-on games to engage students, practice important number sense skills, and to provide opportunities to develop critical thinking skills that many games (within their strategic nature) offer. So what now? What happens in our online digital classrooms? Do we give students access to online games? What are the benefits or drawbacks?

I’ll start off by mentioning that as teachers, using online mathematics games in the classroom can be a good way to consolidate skills. Students often enjoy the challenges and levels that games provide. Note that this time-pressure may also have negative effects on some students, every student is different. Right now, we may not have the ability to play hands-on games so easily when learning is online, can online games be a good replacement for these experiences? To investigate this further, I thought I’d share a bit about what I’ve been doing at home with my own kids.

My own kids love playing games in general. We are a household that play Scrabble, Mahjong, Crib, Sequence, Bananagrams, Yhatzee and Code Names (just to name a few!). They also like playing games online with friends like Roblox. Although Roblox isn’t set up to engage students in mathematics (Mindcraft does this a bit more) it does engage them in community and collaboration. Right now, they love playing it most when they can also Facetime their friends and play online together from their own homes. This is what we want to harness for educational purposes, just don’t tell them!

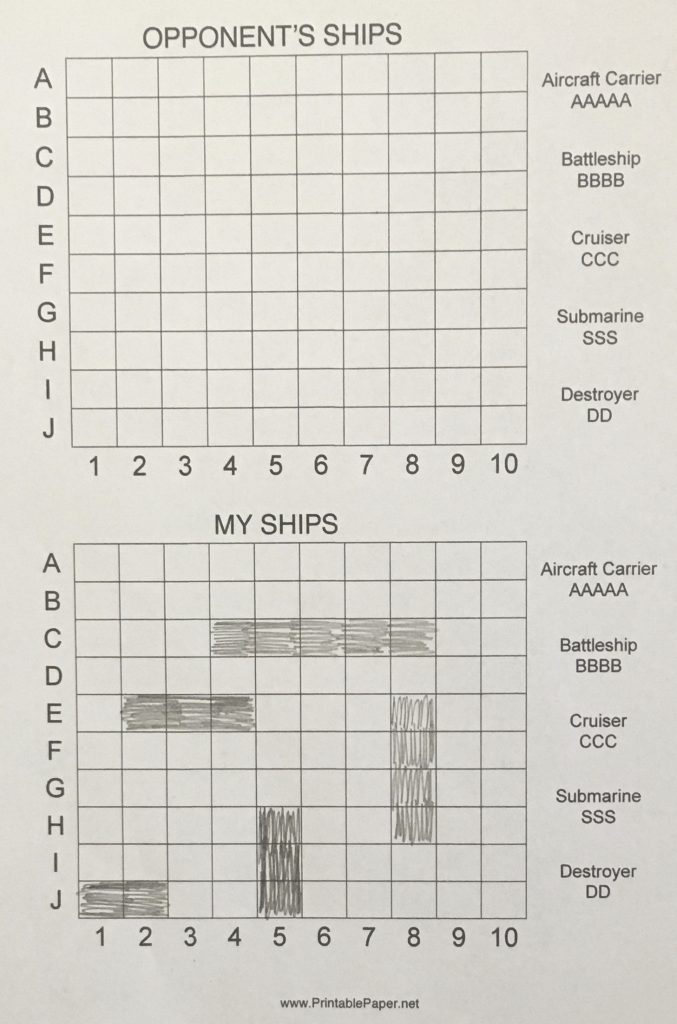

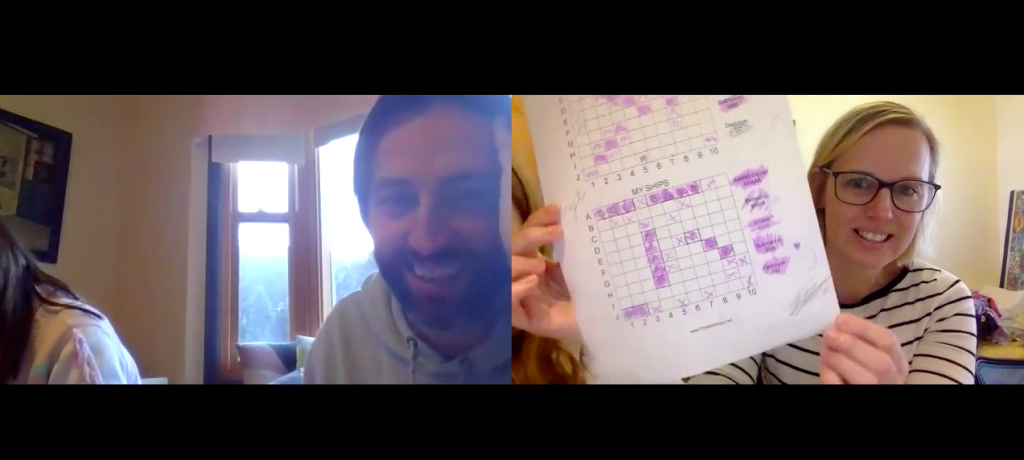

With this in mind, I knew my girls would love to meet up with other kids online to play games. I thought it would be nice to make new friends as well, so I contacted my fellow maths-enthusiast James Russo (@surfmaths). I know he has kids and I thought they might like to play together online. So we decided to play Battleship. This was a classic game from my childhood and it was the first game that popped into my head when I thought about ‘barrier games’. Barrier games work well in the physical classroom as well and this was something I thought would be easy to replicate over Zoom. I sent James and his daughter Lola a Battleship template to print off to play.

It was great! We have played twice, Lola (7 years old) has now played both my youngest daughter Penny (9 years old) and my eldest Lucy (12 years old). Lola won both times, and I’m glad to say there were no tears from our end! We drew the ships on the board (we allowed diagonal placement) then took turns stating the coordinates for each turn. The game continued with lots of ‘misses’ and ‘hits’ and cries of “you sunk my destroyer”, or “you sunk my aircraft carrier”. There is so much mathematics in the game of Battleship. For our young players it involves position, grid coordinates, counting and lots of reasoning. I’ve included here NSW Syllabus content and the Australian Curriculum descriptor that align with Battleship around Position:

Create and interpret simple grid maps to show position and pathways (ACMMG065)

- describe the location of an object using more than one descriptor, eg ‘The book is on the third shelf and second from the left’

- use given directions to follow routes on simple maps

- use and follow positional and directional language (Communicating)

- use grid references on maps to describe position, eg ‘The lion cage is at B3’

- use grid references in games (Communicating)

- identify and mark particular locations on maps and plans, given their grid references

NSW Mathematics syllabus (p. 197)

The girls were happy playing for the fun of it and I was happy we were using technology to socially interact and to (unbeknownst to them) do some mathematics. The conversation was rich with spatial reasoning talk. The girls often said things like “it must be there” or “it can’t go there” or “I already know they’re going to win”. They were getting used to using correct grid referencing such as A3 or J7. I noticed Penny using her fingers to work across and down the rows and columns. She also knew that the ships could not be next to each other so would often work from the playing grid back up to the coordinates in making decisions. The game was long so I think we could speed it up with a smaller board, more ships, or stating near-hit to help students find the ships.

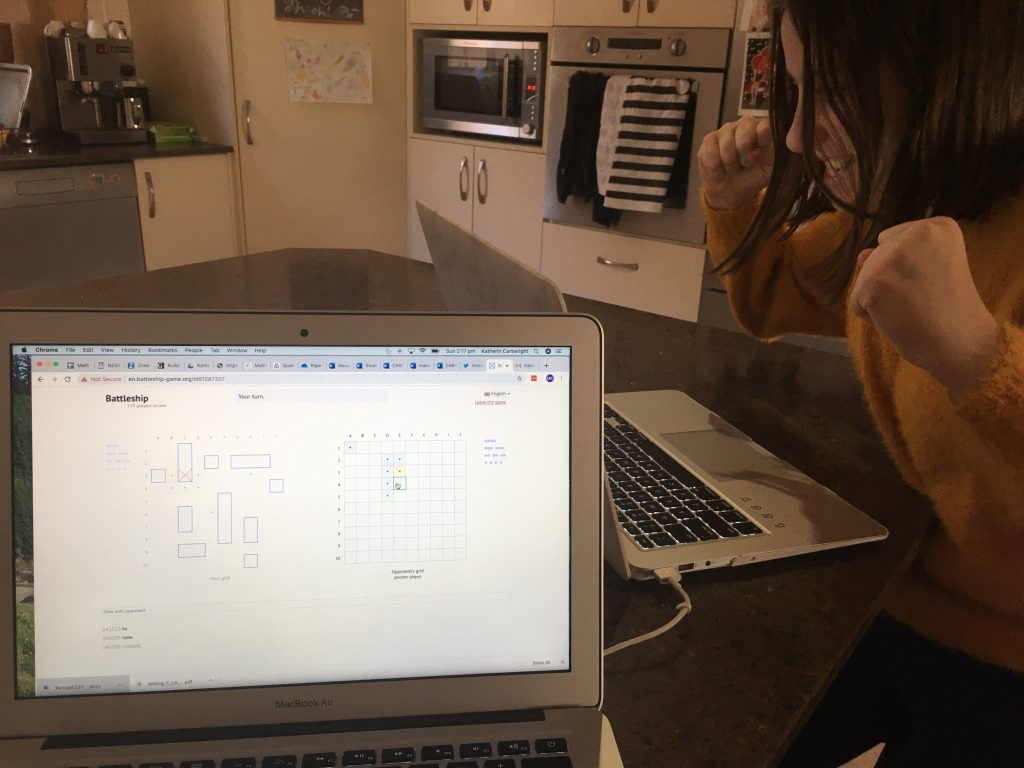

For this game of Battleship we were using technology as the process, not the product. It wasn’t an online game, we were playing the game online. There is a difference. A difference that didn’t really come to light until I played online battleship with Lucy this weekend. I thought that maybe my old-school way of playing ‘over’ the internet, still using paper, might not be as good as using the online version. So I found a version of online Battleship. It’s actually a nice, easy to use version of the game. You pick your ships and send your opponent the link to the game. I’m sure there are other versions or apps for iPad etc but this one served its purpose and Lucy was highly engaged.

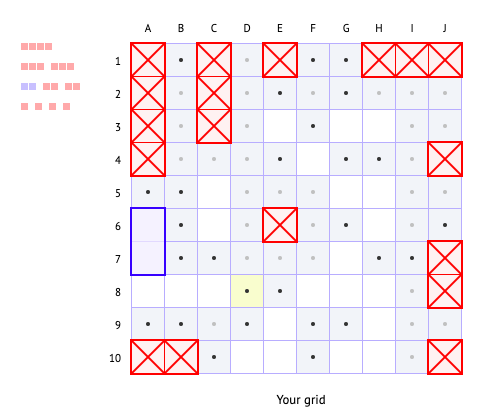

This game was using technology as the product. The game was already designed, we were just playing it online. We played next to each other on two computers which I think added to the fun, being in the same room. There is a chat feature though so you can communicate with your opponent if they are playing from a different location. The biggest think I noticed while paying was the lack of mathematics. As soon as we used the online version, both of us pretty much resorted to just clicking a spot on the grid. There was no talk of grid references as the opponent could see where your guess went on their grid. The game was much quieter as there was n need to state, for example, B5. The game lost a lot of its rich mathematical reasoning both physically and verbally.

Lucy did wonder about how many combinations there were of ‘where the ships could go’ (as you could randomly generate a new board game). She also talked about her reasoning when trying to find the last few ships saying “it can’t go there because that’s only one square and the ship is two squares long”. However, this reasoning conversation would be totally lost if we weren’t playing in the room together.

While I was playing, I did begin to wonder about the mathematics involved in where I ‘guessed’ the ships might be. I definitely thought there must be a mathematical way to do this! Without Googling, I tried to think of a logical way to play. I choose to try picking every second square in each column. This did seem to work for a few games. After playing I was then curious about the actual mathematics and probability behind the game. If this interests you too, Natalie Oldfield’s blog post Mathematics Behind Battleship was a great read. She did mention my strategy as the checkerboard method as well as looking at the way the ships can be arranged at different places on the board – this would make for a great mathematics classroom discussion with students about the probabilities of where the ships might be.

According to Alemi (2011) the reason for the differences in chances of getting a hit is due to the ways in which the ships can be laid out. In the corners the any ship can only be laid out in two different ways, while in the centre there are ten ways.

Natalie Oldfield, Mathematics Behind Battleship, para. 4

For me, the ‘worthiness’ of online games for learning comes down to technology as a process vs product. Although the online version (product) was fun and quick to get ready, most of the mathematics disappeared. Compared to when we used the technology as a conduit to play the game (process), meaning the digital aspects were a way to access the game players, not the game itself. Both have merit and there are times when either of these options – playing an online-game or playing a game online, would be beneficial. If I put my educator hat on though, the drawbacks of online gaming are the isolation of the child from both the mathematical opportunities and the collaborative social interaction. My advice is, if you have the time to play hands-on games online give it a go. There are some other games (not necessarily mathematical) that have crossed the boarder and work well both as a technology product and process, for example, playing online Pictionary-style games like Skribbl.io. I do think they work best though while in Zoom or on the phone for the personal interaction aspect.

When looking to the future of learning and using games, there are some things we are starting to learn. It seems that in these times, when technology use is at its highest, there are still some skills that just develop better using physical learning environments. Some online games will be a hit, and others a miss.

A big THANK YOU to both James and Lola for allowing me to use our game as stimulus for my blog this week.