In light of last week’s SMH article by Jordan Baker regarding private tutoring, I thought this would be a good opportunity to expand on some of the current thinking and discourse surrounding this topic. Being ‘for’ or ‘against’ tutoring is not the ultimate focus for this blog. In fact, as with many aspects of education, it is not about sides, but about the purpose and benefits of the specific idea or issue being discussed. I have endeavoured to highlight both the potential benefits and drawbacks within this piece.

What does the research say?

“The results show that private tutoring has mixed effects depending on how a child feels about and makes use of such support. Hence, the outcome is not always positive.”

Daya Weerasinghe, Monash university

There is limited recent research on mathematics tutoring in an Australian context. Sriprakash, Proctor, and Hu (2015) make the point that although the tutoring industry is on the rise, the research focused on the scale and growth of tutoring is sparse. There is research internationally on tutoring – often termed ‘coaching’ or ‘shadow education’. A study (Lee, 2007) comparing Korea and the United States mentioned culture (beliefs about its importance), academic (achievement and aptitude) and institutional (quality of schooling) factors that influence parents’ choice of tutoring for either enrichment or remediation purposes.

Within the conclusion Lee stated:

“Private tutoring may function as a double-edged sword. On one hand, private tutoring stems from collective needs for providing supplementary education … On the other hand, private tutoring often serves high-achieving students for enrichment or college preparation, which may erode the idea of equal educational opportunities as envisioned by public schooling” (page 1228)

The editor of The shadow education system: private tutoring and its implications for planners, (by Bray, 1999, published by UNESCO the International Institute for Educational Planning) reflects on private tutoring by stating that:

“Training pupils for examination only may not be the best training that can take place. Cramming is often to the detriment of creative learning and may not lead to the expected increase in human capital … Some people also argue that such courses have a negative impact on the mainstream educational system” (page 9)

The author Bray comes to a number of conclusions when comparing tutoring across many countries, one point he makes is that there are mixed results in private tutoring’s effect on school academic achievement and more research is needed on the topic. He suggests that student achievement presumably depends on:

- The content and mode of delivery of the tutoring

- The motivation of the tutors and tutees

- The intensity, duration and timing of the tutoring, and

- The types of pupils who receive the tutoring

Bray also discusses the reported positive and negative impact of tutoring on mainstream classes from a range of European and Asian country contexts:

“When supplementary tutoring helps students to understand and enjoy their mainstream lessons, it may be considered beneficial”

“Supplementary tutoring may also help relatively strong students to get more out of their mainstream classes, exploring various dimensions in greater depth”

“… some students do not pay adequate attention to lessons in the mainstream system … because they have already covered the topics with the tutor”

“… pupils who attended juku were good at computational skills. However, they said that the pupils worked mechanically and without understanding underlying meanings”

Making the decision

The decision whether to send your child to tutoring should be based on what you want your child to gain from the experience.

There is validity in wanting your child to understand the content being learned at school for their age group. When students have areas or gaps in their learning, gaining help for these children to be able to ‘catch up’ or continue at their current level of understanding is important.

Sriprakash, Proctor, and Hu’s (2015) research focuses on interviewing parents of primary school students who attended tutoring in Sydney. Some parents’ choice to send their children to tutoring was based on their ‘visible’ pedagogy, wanting to keep “close supervision of academic work in terms of needing to be alert and informed about their children’s educational progress” (p. 433). Parents saw tutoring as an opportunity to know what their children were doing particularly in cases where homework was not given to their children from school. “Without this visible practice, parents expressed they were left out of their children’s learning” (p. 434).

This is an interesting point, and one we as classroom teachers need to attend to. If we are choosing to not send homework home, what alternative mechanisms are in place to keep communication lines open to parents about what is going on in the classroom? Also, the types of homework we send home inform parents of what learning looks like in the classroom.

Moving away from more traditional ‘textbook’ or ‘mentals’ style homework in primary settings is (in my opinion) valid. Changing our homework practices aligns with our mathematics curriculum that focuses on how students apply, reason and problem solve using the knowledge, not just having the knowledge itself. However, in the absence of any homework, where does this leave parents? They still need information and students still often require rehearsal or consolidation (through practice), but it’s what they are practicing that needs to change. This imbalance needs to be addressed.

The decision for tutoring is sometimes made with the rationale of ‘getting ahead’ or “securing their children’s academic success” (Sriprakash et al., 2015, p. 437) when applying for OC (opportunity class) or scholarships or academically selective high schools. As the choice is a personal choice, this is also a valid reason. Tutoring of this kind may assist in the short term, but I wonder, what does it mean for the child’s relationship with the subject (mathematics) itself, and also for their relationship with learning?

Learning is a life-long endeavour that needs to be embraced as not a means to an end but as a self-satisfying experience where thinking in different ways and cherishing ‘a-ha’ moments of success in gaining understanding are valued in their own right.

We want students to continue to love learning beyond the classroom, if learning seems like a chore, this love of learning may not spark joy – but spark anxiety.

Catherine Attard’s (2015) research into student engagement highlights three aspects of engagement: operative, cognitive and affective, where students are “feeling good, thinking hard and actively participating” (para. 1). Working together, these domains of engagement can increase students’ self-belief as learners as they engage thoughts, actions and feelings towards the learning at hand. For mathematics, this is especially important as low self-belief (of themselves as learners) and a lack of self-efficacy (confidence of their ability) is identified as having a huge impact on a student’s success.

Questions to consider

With this in mind, here are a few questions to think about in choosing mathematics tutoring:

- Is the focus of the tutoring increasing the child’s enjoyment of the subject?

- Does the tutoring allow time for the child to think deeply about the concepts or is it more about learning procedures and rules?

- Does the tutoring focus on problem solving and using knowledge in new and varied contexts?

- Is there a focus on developing a variety of ways to solve tasks and/or finding multiple solutions or alternative solutions?

- Is there a focus on communicating how and why the mathematics works?

- Is the tutor excited by mathematics? Do they have a passion for it?

- Are the children working together? Or is all the work individual?

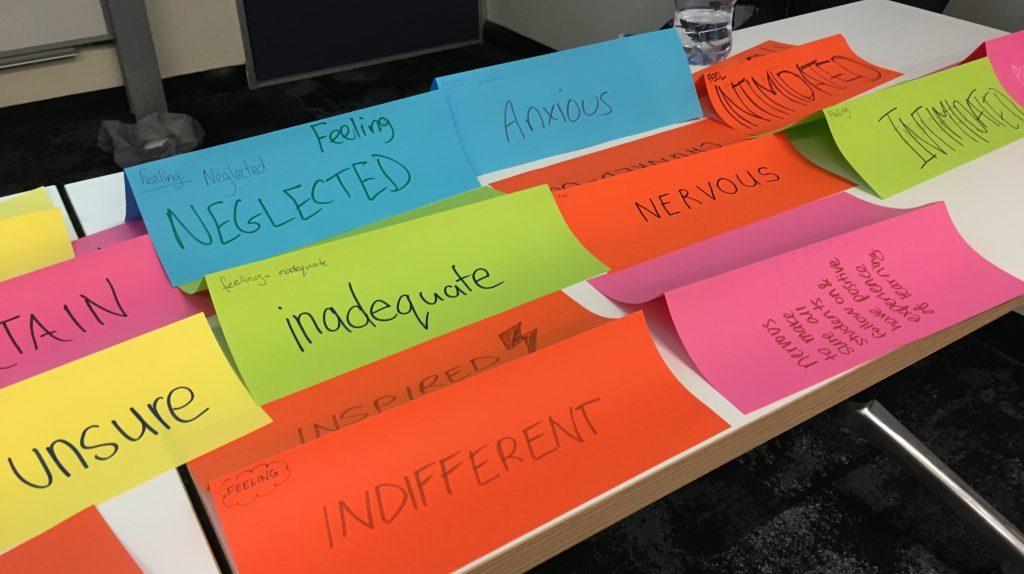

These are important questions to consider. At university, when teaching primary education pre-service teachers we spend time discussing how they feel about mathematics itself and how they feel about getting ready to teach mathematics.

In regards to mathematics itself, there is a wide scale of feelings from ‘awe’ and ‘fun’ through to ‘anxious’ and ‘intimidated’. There are students at both ends of this scale that have had experience with tutoring at school. Some already had a love for mathematics and the tutoring grew that love, while others felt the tutoring, while improving their school results, didn’t make maths any clearer for them.

Content is important but if you’ve learned maths as a disconnected set of rules and procedures, you probably don’t feel very confident.

It is this latter issue that we need to be mindful of when it comes to tutoring. It can have a great impact and result in success for many students. However, if students experience success yet still feel their knowledge of mathematics is inadequate or that there is much of mathematics they do not really understand (even though they can ‘do’ it) then this is of wider concern.

We want them to like and understand maths, not just to be able to do it.

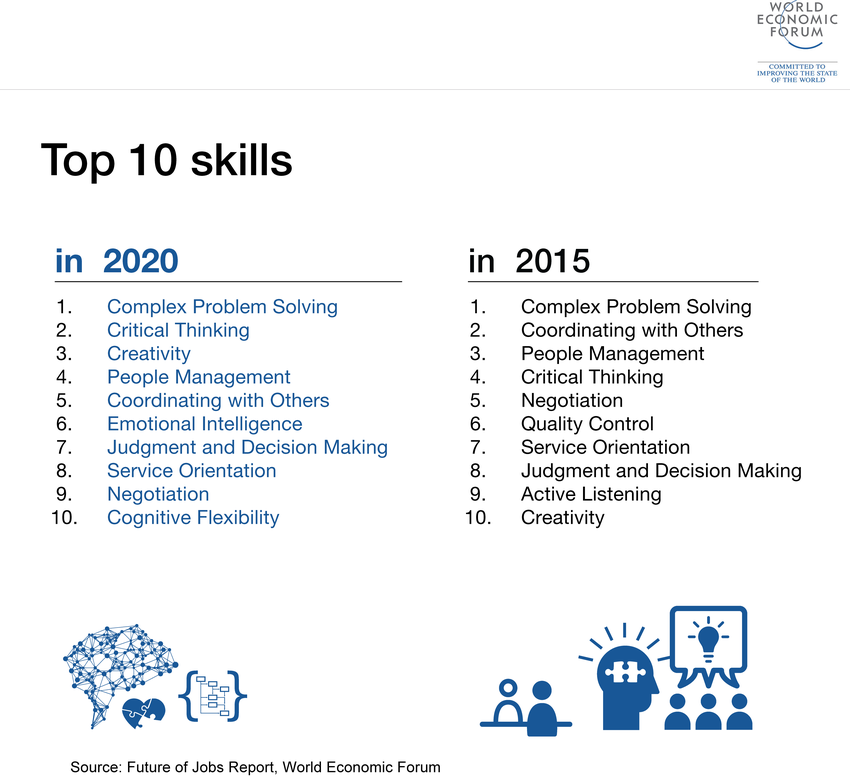

Learning ‘harder maths’ or secondary level maths while in primary school may provide children with the content and procedures, but they need time to develop skills in reasoning, justifying and communicating, in life there isn’t normally a test. It’s applying what you know in a variety of situations. What we learn is really only useful if we can communicate this knowledge with others. In the work environment the focus is on collaboration, problem finding and problem solving, taking initiative and applying knowledge.

So the question is, is tutoring preparing children for life and the workforce? Or is it just preparing them for the next test?

References

Catherine Attard, Engaging children with mathematics: Are you an engaged teacher? Accessed on 21 June 2019 from https://engagingmaths.com/category/learning/

Attard, C. (2015). Engagement and mathematics: What does it look like in your classroom. Journal of Professional Learning, Semester, 2. Accessed on 5 May from https://cpl.asn.au/sites/default/files/journal/Catherine%20Attard%20%20-%20Engagment%20and%20Mathematics.pdf

Attard, C. (2014). “I don’t like it, I don’t love it, but I do it and I don’t mind”: Introducing a framework for engagement with mathematics. Curriculum Perspectives, 34(3), 1-14.

Bray, T. M. (1999). The shadow education system: Private tutoring and its implications for planners. UNESCO International Institute for Educational Planning.

Lee, J. (2007). Two worlds of private tutoring: The prevalence and causes of after-school mathematics tutoring in Korea and the United States. Teachers College Record, 109(5), 1207-1234.

Sriprakash, A., Proctor, H., & Hu, B. (2015). Visible pedagogic work: parenting, private tutoring and educational advantage in Australia. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 37(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2015.1061976

Weerasinghe, D. (2018) Provision of private tutoring while school teachers provide enough support in mathematics education, short communication at MERGA 41, Making waves, opening spaces (Proceedings of the 41st annual conference of the Mathematics Education Research Group of Australasia), Auckland.