Teaching is hard work, and learning isn’t easy. It is time to appreciate the complexity of the job and to talk about the real purpose of education, to improve student learning. Actually, it could be better phrased as to improve an individual’s learning. Something that all teachers work hard to achieve. To help students move from where they are now, to where to next – the next step in their learning along the journey.

A colleague reminded me this week that a GP treats one client at a time, a teacher is teaching up to 30+ at once. This makes teaching a complex job, more akin to that of an Emergency room in a hospital. There are urgent needs that require triage, needs that at first may not be easy to recognise, and needs that once addressed result in immediate improvement.

Doctors aren’t judged by their patients’ abilities to get well or by how many patients each year are cured, as the patients are different from year to year. Bank managers aren’t judged by how well their customers save money or by how many of their customers have the most money in the bank. However, teachers are constantly scrutinised based on how well their students perform in standardised test, and standardised tests over time. Each year brings a different cohort of students with different needs and differing external factors to their learning.

Although those outside the classroom are focusing on scores and comparing students in international testing such as PISA or TIMSS, teachers within the classroom are focused on growth. One of the best aspects of NAPLAN data that schools can analyse, is the growth graphs. These graphs indicate the growth of each student from say their Year 3 to Year 5 NAPLAN for each area assessed. The information gathered here is a much better indication of the success of students. It allows schools to make note of any specific students that may require more support, or further extension to grow in their learning. Growth data can also pinpoint trends over time. For example, is a school improving learning for their most needy students, but high achieving students are not making any growth?

Unfortunately, growth is not the main focus of those creating league tables based on the My School website data in comparing schools. They generally compare the percentage in bands, not student gain. At a school, you could have many students in the top band, but if their growth is small, what have they been learning? What difference has been made for them as individual students? We know that not all students start (or finish) at the same place on the learning continuum, so judging their end point alone is not sufficient. Growth and improvement are important.

“Students who believe that intelligence or math and science ability is simply a fixed trait (a fixed mindset) are at a significant disadvantage compared to students who believe that their abilities can be developed (a growth mindset).”

Carol Dweck, Mindsets and Math/Science Achievement, page 2

In the primary school setting, we have a high focus on growth and for students to see that when you put effort in, you succeed. We often talk about learning intentions (goals) and success criteria (how to get there). Carol Dweck’s work around Growth Mindset and the importance of students not seeing their intellect as fixed, is part of contemporary pedagogy. When students say “I don’t know how to do that” the addition of the word “yet” at the end encourages students to see that with hard work, practice and effort, our intelligence can change and grow. Learning isn’t always easy. For some of us certain concepts may come easier, but for the areas where it doesn’t, we can still succeed. This requires perseverance and a growth mindset.

I think this is also what parents want for their children. We do not send them to school saying, “beat everyone else” or “you need to come first” (hopefully!). We tell our children to “do their best”, to “do their personal best”. The outcome of this mindset may indeed result in success above others, but that is not the goal we start with. As students move closer to the HSC, the personal goal of growth achievement (journey goal) is sometimes clouded by a want or pressure to attain top bands (end goal).

The current climate in educational discussions seems to be more focused on how to ‘fix things’ and specifically, the teachers. Whether it be higher levels of entry to education, higher levels of exiting their education, or accountability through more testing of their students, these all miss the point. Teaching is hard. Teaching is complex. Students’ needs are complex, and their development does not follow a consistent linear pathway. High scoring teachers do not automatically equate to high scoring students. Teaching is as much about passion and student-teacher relationships as it is about knowledge.

A good teacher is not one that knows everything, but one who sees themselves as a learner. When you see yourself as a learner, you can empathise with your students. You can model what learning looks like, you can guide students with effective questioning, and you can use appropriate challenge to develop them as independent learners. The skill of being able to break a concept down into smaller parts to learn and to make connections between students’ prior knowledge and new understandings is an artform. It is a balancing act between teaching students and letting them learn. Just because you can ‘do the math’ does not necessarily mean you can teach someone else.

#growthmindset never stop learning! pic.twitter.com/cALhZ1YU3u

— Anne Keith (@MTTeacherCoach) February 22, 2020

#RESCON19 @Sciencesteveg Great presentation thanks Steve - reaching every student is aspirational but worth the effort pic.twitter.com/pLy2cqFIwE

— Tracey muir (@muir_tracey) October 19, 2019

I read an article in the Sydney Morning Herald this week where the NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian suggested one-size-fits-all teaching practices across our schools. The article acknowledges that teachers and experts warned that this approach was not suitable due to differing needs of students and that teacher judgement was key. In fact, our NESA NSW syllabuses states that teachers should be the ones making the decisions:

“In considering the intended learning, teachers [emphasis added] will make decisions about the sequence, the emphasis to be given to particular areas of content, and any adjustments required based on the needs, interests and abilities of their students.”

NESA mathematics syllabus, organisation of content

The adjustments teachers make are a necessary part of teaching. I disagree with the article and the statement that teachers should not have access to “a suite of things to consider when teaching children”. That is exactly what is needed, a suite of effective teacher practices. Teachers use a range of strategies, adapting and changing practices dependent on student need. If we are focusing on individual students and differentiating practices to assist all student learning, then I would go as far to say that it is essential that teachers are flexible and that teaching practices are not all the same. Consistent practices yes, singular practices no. The article goes on to highlight this sentiment – teacher choice is imperative. If we lose teacher-choice, we lose teacher judgement and professionalism.

The plan in the article “to use the department’s data to find schools that were excelling in different areas” probably rings alarm bells for most teachers. As mentioned above in my blog, if we just look at percentage in top bands in NAPLAN, this will not necessarily provide you with teachers or school that are using research-based, evidence-based, contemporary teaching pedagogy. Any teacher could ‘train’ students to do well in NAPLAN, but schools or teachers who are able to create student growth – that’s what you want to be looking for. Research involving NAPLAN data to find ‘successful schools’ or ‘best practice’ has actually already been completed. Research that focused-on growth, specifically related to numeracy was undertaken in 2016. See Achieving growth in NAPLAN: characteristics of successful schools authored by Muir, Livy, Herbert and Callingham in the references section.

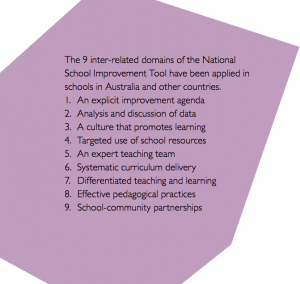

As reported on in the Muir et al. (2016) paper, the most influential characteristics on student growth included intentional school-wide policies to support growth, consistent approaches to teaching, team planning and the use of several data sources to plan next steps. Note the word ‘approaches’ not approach. Time and professional learning allocated for teacher collaboration and sharing of resources can provide a gateway to consistency across classrooms. In a more recent paper by Muir, Livy, Herbert and Callingham (2018) they reiterated the same findings adding that the domains of the Teaching and Learning School Improvement Framework (Masters, 2010) was a good tool in identifying areas and strategies for improvement. Overall, there is no one program or process that fits education. Just like there is no one medicine or course of action that suits all patients.

Whatever the future holds for education, a focus on working alongside teachers to improve student learning and growth is needed, not looking for reasons why teachers have failed or how to get better test results on a single assessment measure.

References

Callingham, R., Anderson, J., Beswick, K., Carmichael, C., Geiger, V., Goos, M., … & Page, L. (2018). Nothing left to chance: Characteristics of schools successful in mathematics. Report of the Developing an Evidence Base for Best Practice in Mathematics in Education Project.

Callingham, R., Carmichael, C., & Watson, J. M. (2016). Explaining student achievement: The influence of teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge in statistics. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 14(7), 1339-1357.

Dweck, C. S. (2014). Mindsets and math/science achievement. http://www.growthmindsetmaths.com/uploads/2/3/7/7/23776169/mindset_and_math_science_achievement_-_nov_2013.pdf

Masters, G. N. (2010). Teaching and learning school improvement framework https://research.acer.edu.au/tll_misc/21/

Muir, T., Livy, S., Herbert, S., & Callingham, R. (2016, January). Achieving growth in NAPLAN: characteristics of successful schools. In AARE 2016: Transforming educational research: Proceedings of the Conference for the Australian Association for Research in Education: Transforming Education Research (pp. 1-12). AARE.

Muir, T., Livy, S., Herbert, S., & Callingham, R. (2018). School leaders’ identification of school level and teacher practices that influence school improvement in national numeracy testing outcomes. The Australian Educational Researcher, 45(3), 297-313.