Dear Mum and Dad

I have been going through a box of my mother’s. She was a hoarder, and the box contained mementos from her life. And ours.

When we were young we made our own birthday, Christmas, and Fathers’ and Mothers’ Day cards. The ones I found had mostly been created on simple lined paper from a writing pad, with a simple greeting.

They were perfect examples of the development of understanding as we children learned the formalities of writing.

These cards began with ‘Dear Father’, ‘Dear Mother’, and my sister tried ‘Dear Mr Rowell’. These eventually became ‘Dear Daddy’, ‘To Mummy’, and ‘Hi Dad,’ as we grew more confident with our relationship with our parents, and with our writing. Mum was always ‘Dear Mum’.

That tells enough about us and our parents.

People on the beach

The way artists can capture a figure, way off in the distant curve of the beach, or fishing, or sitting or lying on the sand, hunched or splayed, has always delighted me. A few swift strokes of colour, of light and dark paint, and there is a strolling couple, a jogger, a group talking animatedly.

How can we capture that in words?

How to write people

We learn about people by looking at people, by having experiences with them, by having a growing number of people in our circles of relatives, acquaintances and friends. We know these people in ways that often aren’t, and frequently can’t be, clearly or easily articulated.

How can we capture them in words?

Authors do it all the time, often with the same type of swift strokes, of colour and lights and darks. We can use these in the classroom, at every Stage, to build students’ understanding of the power of individual words, and the power of combining words to create characters.

We can introduce a character and respond to the words the author has used.

Examples:

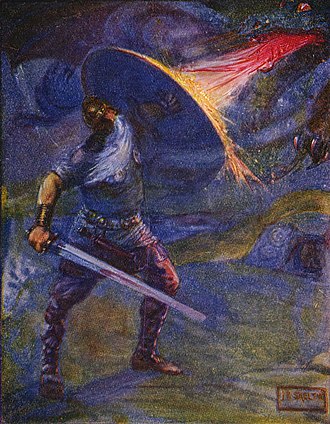

Then the hero, stern under his gleaming helmet,

With his stout mailcoat and thick-plated shield,

Strode out to meet his foe.

From Beowulf and the Dragon, translated by Ian Serraillier

How do we KNOW Beowulf is brave?

Key words ABOUT this character: hero, stern, strode out;

These can used for discussion, and for building word clines and word maps, all considering positive and negative implications of the words, together with synonyms and antonyms, and degrees of intensity –

eg: stern, serious, angry, pleasant, happy, determined, fierce, shocked, mournful, weak, sad, etc

- What is the impact on meaning if we substitute each word in the original text?

- Beowulf was going out to meet a dragon, ‘his foe’. Where do we show sternness? Where might a person in your life have to go, being ‘stern’? Could you be stern and laughing at the same time? Why/not? Who do you know who is ‘stern’? Are they always? Are you ever stern?

- ‘Stern’ and ‘strode out’ are put together. Why did the author do this?

- Collect other walking words, and arrange them in a cline from low intensity to strong intensity – not necessarily based on speed of the movement:

- stride, walk, dawdle, step, pace, stride, strut, prance, tip-toe, leap, stamp, lurch, waddle, stumble

- What is the impact on meaning if we substitute each word in the original text?

- Beowulf’s manner is supplemented by: gleaming helmet, stout mailcoat, thick-plated shield

What is the effect of these descriptions? What substitutions could we make to alter the image we have built of Beowulf facing his foe?

Suggestion:

Use the original excerpt to construct a description of a person in your life heading out somewhere.

You can play with this – it might be driving into the car park at Westfields, or a student going to their first day of school, getting into the pool for training, buying toilet paper at the supermarket, taking a sick person the hospital – talk about when parents have been stern, or make it into something entertaining.

Other authors

Others build the picture of the character by using lots of words to create the image:

Their teacher was called Miss Honey, and she could not have been more than twenty-three or twenty-four. She had a lovely pale oval Madonna face with blue eyes and her hair was light brown. … Some curious warmth that was almost tangible shone out of Miss Honey’s face when she spoke to a confused and homesick newcomer to the class.

Roald Dahl (1988) Matilda Guild Publishing London p.66-67

Use this as a model – pull out the noun groups, examine the adjectives that Dahl used – how do we KNOW Miss Honey is lovely?

Use any one of readers’ favourite characters who have been invented by authors, and who have almost become real. Read the books to your students so these characters can become part of their worlds too – Anne Shirley, Coraline, Alice, Gilly Hopkins, Hermione Harry and Ron, Pippi Longstocking, Charlie, Amelia Bedelia, Princess Smartypants, Mr. Chicken, Dora the Explorer, Tintin and Sooty, Thomson and Thompson, Dorothy and Toto – and the thousands of others waiting inside the covers of the books available to us.

They all have a place in the reading lives of our students.

Our own people

It can be difficult to get enough distance between ‘our’ people to be able to describe them. Students need the words.

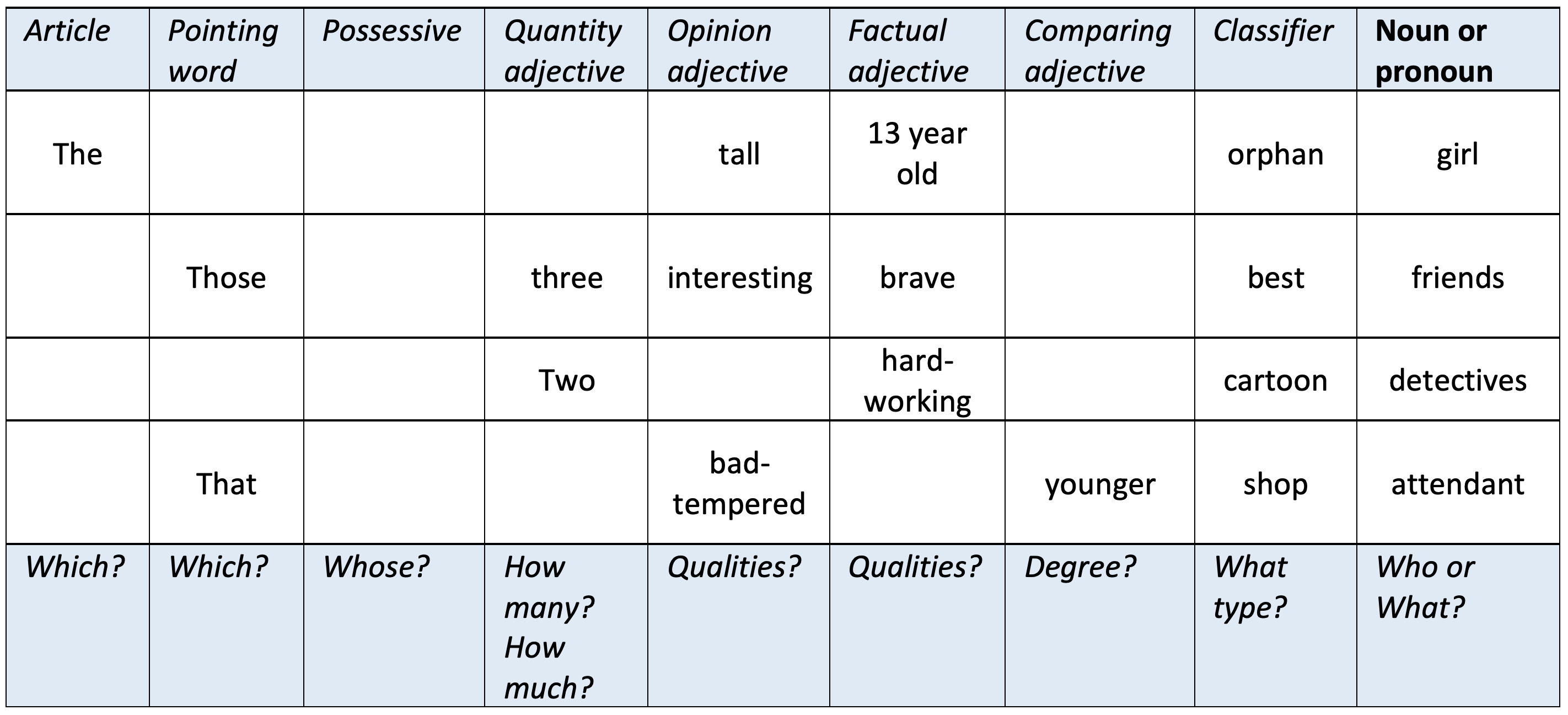

There is an excellent activity in Derewianka’s Exploring how texts work 2nd Editiion PETAA (2011) which demonstrates the ways noun groups can be built. It consists of a table that can be completed for any noun group, using pre-modifiers. Try it with fictional characters before moving on to either people they know, or their own creations:

We guide our students to learn what an appropriate greeting is to a parent on a birthday card, or to the Principal of the school, or to a Member of Parliament, or on a home- made card for a favourite aunt for her birthday. We teach our students who would call their mother ‘Mum’, or ‘Dear Carol’, or ‘Darling’, or ‘Ms Cavalier’, or ‘Madame,’ or ‘To whom it may concern’, or ‘Dear Professor Cavalier’, or ‘Your Honour’.

This stuff is important, even after so many years for my mother’s treasures to come to light, and make us all laugh.

It is the compelling nature of stories and their telling that that impacts on how we relate to each other, how we define who we are, and how and what we learn.

Libby Gleeson Writing like a Writer (2007) PETA